BYzantine EMpire tactics

After Rome fell, the Byzantine empire continued to survive for hundreds of years. The change in location, leadership, and resources caused the tactics to change from the original Roman ones.

By the time of the so-called Byzantine era (the surviving eastern Roman empire) true power on the battle field had long since passed into the hands of the cavalry. If there was any infantry, it was made up of archers, whose bows had longer range than the smaller bows of the horsemen.

Handbooks were published, most famously by the general and later emperor Maurice (the strategicon), the emperor Leo VI (the tactica) and Nicephorus Phocas (the updated tactica).

As with the old Roman legion, the infantry still fought at the centre, with the cavalry at the wings. But often now the lines of the infantry stood further back than the cavalry wings, creating a 'refused' centre. Any enemy who would try and attack the infantry would have to pass between the two wings of the cavalry.

In hilly ground or in narrow valleys where the cavalry could not be used, the infantry itself had its lighter archers at the wings, whereas its heavier fighters (scutati) were placed at the centre. The wings were positioned slightly forward, creating a kind of crescent-shaped line.

In case of an attack on the centre of the infantry the wings of archers would send a storm of arrows upon the attacker. Though in case the infantry wings themselves were attacked they could retire behing the heavier scutati.

Often though infantry was not part of the conflict at all, with commanders relying entirely on their cavalry to win the day.

It is in the tactics described for these occasions that the sophistication of Byzantine warfare becomes apparent.

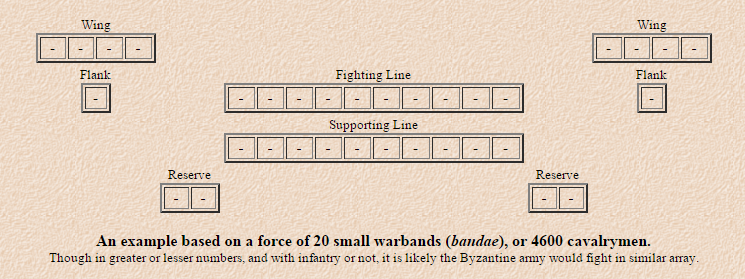

The manuals indicate that a cavalry force fought in a formation looking much like this.

By the time of the so-called Byzantine era (the surviving eastern Roman empire) true power on the battle field had long since passed into the hands of the cavalry. If there was any infantry, it was made up of archers, whose bows had longer range than the smaller bows of the horsemen.

Handbooks were published, most famously by the general and later emperor Maurice (the strategicon), the emperor Leo VI (the tactica) and Nicephorus Phocas (the updated tactica).

As with the old Roman legion, the infantry still fought at the centre, with the cavalry at the wings. But often now the lines of the infantry stood further back than the cavalry wings, creating a 'refused' centre. Any enemy who would try and attack the infantry would have to pass between the two wings of the cavalry.

In hilly ground or in narrow valleys where the cavalry could not be used, the infantry itself had its lighter archers at the wings, whereas its heavier fighters (scutati) were placed at the centre. The wings were positioned slightly forward, creating a kind of crescent-shaped line.

In case of an attack on the centre of the infantry the wings of archers would send a storm of arrows upon the attacker. Though in case the infantry wings themselves were attacked they could retire behing the heavier scutati.

Often though infantry was not part of the conflict at all, with commanders relying entirely on their cavalry to win the day.

It is in the tactics described for these occasions that the sophistication of Byzantine warfare becomes apparent.

The manuals indicate that a cavalry force fought in a formation looking much like this.

Specific Byzantine TacticsThe Byzantine art of war was highly developed and eventually even contained specially developed tactics for specific opponents.

Leo VI's manual, the famous tactica, provides precise instructions for dealing with various foes.

The Franks and the Lombards were defined as knightly heavy cavalry which, in a direct charge, could devastate an opponent and so it was advised to avoid a pitched battle against them. However, they fought with no discipline and little to no battle order at all and generally had few, if any, of their horsemen performing any reconnaissance ahead of the army. They also failed to fortify their camps at night.

The Byzantine general would hence best fight such an opponent in a series of ambushes and night attacks. If it came to battle he would pretend to flee, drawing the knights to charge his retreating army - only to run into an ambush.

The Magyars and Patzinaks, referred to as the Turks by the Byzantines, fought as bands of light horsemen, armed with bow, javelin and scimitar. They were accomplished in performing ambushes and used many horsemen to scout ahead of the army.

In battle they advanced in small scattered bands which would harass the frontline of the army, charging only if they discovered a weak point.

The general was advised to deploy his infantry archers in the front line. Their larger bows had greater range than that of the horsemen and could so keep them at a distance. Once the Turks, harassed by the arrows of the Byzantine archers would try and close into range of their own bows, the Byzantine heavy cavalry was to ride them down.

The Slavonic Tribes, such as the Servians, Slovenes and Croatians still fought as foot soldiers. However, the craggy and mountainous terrain of the Balkans lent itself very well to ambushes by archers and spearmen from above, when an army would be hemmed in in a steep valley. Invasion into their territories was hence discouraged, though if necessary, it was recommended that extensive scouting was undertaken in order to avoid ambushes.

However, when hunting down Slavonic raiding parties or meeting an army in open field, it was pointed out that the tribesmen fought with little or no protective armour, except for round shields. Hence their infantry could easily be overpowered by a charge of the heavy cavalry.

The Saracens were judged as the most dangerous of all foes by Leo VI. Had they in earlier centuries been powered only by religious fanaticism, then by the time of Leo VI's reign (AD 886-912) they had adopted some of the weaponry and tactics of the Byzantine army.

After earlier defeats beyond the mountain passes of the Taurus, the Saracens concentrated on raiding and plundering expeditions instead of seeking permanent conquest. Having forced their way through a pass, their horsemen would charge into the lands at an incredible speed.

Byzantine tactics were to immediately collect a force of cavalry from the nearest themes and to trail the invading Saracen army. Such a force might have been too small to seriously challenge the invaders, but it deterred small detachments of plunderers from breaking away from the main army.

Meanwhile the main Byzantine army was to be gathered from all around Asia Minor (Turkey) and to meet the invasion force on the battlefield.

The Saracen infantry was deemed by Leo VI to be little more than an disorganized rabble, except for the occasional Ethiopian archers who though were only lightly armed and hence could not match the Byzantine infantry.

If the Saracen cavalry was judged to be a fine force it could not match the discipline and organisation of the Byzantines. Also the Byzantine combination of horse archer and heavy cavalry proved a deadly mix to the light Saracen cavalry.

Should however, the Saracen force only be caught up with by the time it was retreating homewards laden with plunder, then the emperor Nicephorus Phocas advised in his military manual that the army's infantry should set upon them at night from three sides, leaving open only the road back to their land. It was deemed most likely that the startled Saracens would leap to their horses and take homeward rather than defend their plunder.

Another tactic was to cut off their retreat across the passes. Byzantine infantry would reinforce the garrisons in the fortresses guarding the passes and the cavalry would pursue the invader driving them up into the valley. Like this the enemy could be helplessly pressed into a narrow valley with little to no room to manoeuver. Here they would be easy prey to the Byzantine archers.

A third tactic was to launch counter attack across the border into Saracen territory. An invading Saracen force would often turn around to defend its own borders if message of an attack reached it.

Leo VI's manual, the famous tactica, provides precise instructions for dealing with various foes.

The Franks and the Lombards were defined as knightly heavy cavalry which, in a direct charge, could devastate an opponent and so it was advised to avoid a pitched battle against them. However, they fought with no discipline and little to no battle order at all and generally had few, if any, of their horsemen performing any reconnaissance ahead of the army. They also failed to fortify their camps at night.

The Byzantine general would hence best fight such an opponent in a series of ambushes and night attacks. If it came to battle he would pretend to flee, drawing the knights to charge his retreating army - only to run into an ambush.

The Magyars and Patzinaks, referred to as the Turks by the Byzantines, fought as bands of light horsemen, armed with bow, javelin and scimitar. They were accomplished in performing ambushes and used many horsemen to scout ahead of the army.

In battle they advanced in small scattered bands which would harass the frontline of the army, charging only if they discovered a weak point.

The general was advised to deploy his infantry archers in the front line. Their larger bows had greater range than that of the horsemen and could so keep them at a distance. Once the Turks, harassed by the arrows of the Byzantine archers would try and close into range of their own bows, the Byzantine heavy cavalry was to ride them down.

The Slavonic Tribes, such as the Servians, Slovenes and Croatians still fought as foot soldiers. However, the craggy and mountainous terrain of the Balkans lent itself very well to ambushes by archers and spearmen from above, when an army would be hemmed in in a steep valley. Invasion into their territories was hence discouraged, though if necessary, it was recommended that extensive scouting was undertaken in order to avoid ambushes.

However, when hunting down Slavonic raiding parties or meeting an army in open field, it was pointed out that the tribesmen fought with little or no protective armour, except for round shields. Hence their infantry could easily be overpowered by a charge of the heavy cavalry.

The Saracens were judged as the most dangerous of all foes by Leo VI. Had they in earlier centuries been powered only by religious fanaticism, then by the time of Leo VI's reign (AD 886-912) they had adopted some of the weaponry and tactics of the Byzantine army.

After earlier defeats beyond the mountain passes of the Taurus, the Saracens concentrated on raiding and plundering expeditions instead of seeking permanent conquest. Having forced their way through a pass, their horsemen would charge into the lands at an incredible speed.

Byzantine tactics were to immediately collect a force of cavalry from the nearest themes and to trail the invading Saracen army. Such a force might have been too small to seriously challenge the invaders, but it deterred small detachments of plunderers from breaking away from the main army.

Meanwhile the main Byzantine army was to be gathered from all around Asia Minor (Turkey) and to meet the invasion force on the battlefield.

The Saracen infantry was deemed by Leo VI to be little more than an disorganized rabble, except for the occasional Ethiopian archers who though were only lightly armed and hence could not match the Byzantine infantry.

If the Saracen cavalry was judged to be a fine force it could not match the discipline and organisation of the Byzantines. Also the Byzantine combination of horse archer and heavy cavalry proved a deadly mix to the light Saracen cavalry.

Should however, the Saracen force only be caught up with by the time it was retreating homewards laden with plunder, then the emperor Nicephorus Phocas advised in his military manual that the army's infantry should set upon them at night from three sides, leaving open only the road back to their land. It was deemed most likely that the startled Saracens would leap to their horses and take homeward rather than defend their plunder.

Another tactic was to cut off their retreat across the passes. Byzantine infantry would reinforce the garrisons in the fortresses guarding the passes and the cavalry would pursue the invader driving them up into the valley. Like this the enemy could be helplessly pressed into a narrow valley with little to no room to manoeuver. Here they would be easy prey to the Byzantine archers.

A third tactic was to launch counter attack across the border into Saracen territory. An invading Saracen force would often turn around to defend its own borders if message of an attack reached it.

All credit and sourcing to: http://www.roman-empire.net/army/tactics.html