sTRATEGY

The first strategy was actually employed before any fighting took place at all. Religion and ritual were important features of Greek life, and before embarking on campaign, the will of the gods had to be determined. This was done through the consultation of oracles such as that of Apollo at Delphi and through animal sacrifices (sphagia) where a professional diviner (manteis) read omens (ta hiera), especially from the liver of the victim and any unfavourable signs could certainly delay the battle. Also, at least for some states like Sparta, fighting could be prohibited on certain occasions such as religious festivals and for all states during the great Panhellenic games (especially those at Olympia).

When all of these rituals were out of the way, fighting could commence but even then it was routine to patiently wait for the enemy to assemble on a suitable plain nearby. Songs were sung (the paian - a hymn to Apollo) and both sides would advance to meet each other. However, this gentlemanly approach in time gave way to more subtle battle arrangements where surprise and strategy came to the fore. What is more, conflicts also became more diverse in the Classical period with sieges and ambushes, and urban fighting becoming more common, for example at Solygeia in 425 BCE when Athenian and Corinthian hoplites fought house to house.

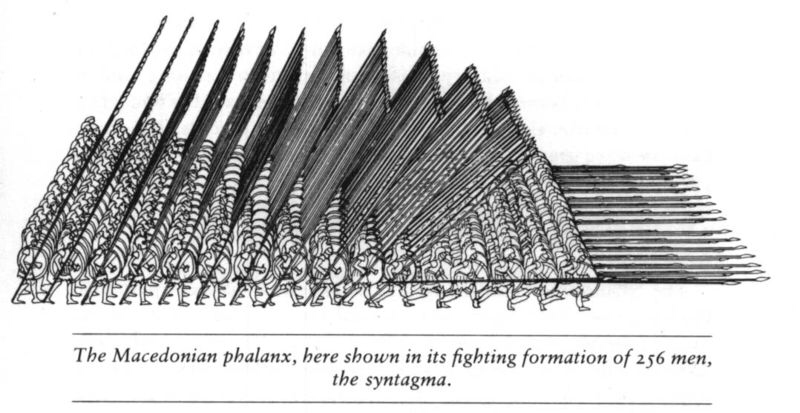

Strategies and deception, the ‘thieves of war’ (klemmata), as the Greeks called them, were employed by the more able and daring commanders. The most successful strategy on the ancient battlefield was using hoplites in a tight formation called the phalanx. Each man protected both himself and partially his neighbour with his large circular shield, carried on his left arm. Moving in unison the phalanx could push and attack the enemy whilst minimising each man’s exposure. Usually eight to twelve men deep and providing the maximum front possible to minimise the risk of being outflanked, the phalanx became a regular feature of the better trained armies, particularly the Spartans. Thermopylae in 480 BCE and Plataea in 479 BCE were battles where the hoplite phalanx proved devastatingly effective.

At the Battle of Leuktra in 371 BCE Thebian general Epaminondas greatly strengthened the left flank of his phalanx to about 50 men deep which meant he could smash the right flank of the opposing Spartan phalanx, a tactic he used again with great success at Mantineia in 362 BCE. Epaminondas also mixed lighter armed troops and cavalry to work at the flanks of his phalanx and harry the enemy. Hoplites responded to these developments in tactics with new formations such as the defensive square (plaision), used to great effect (and not only in defence) by Spartan general Brasidas in 423 BCE against the Lyncestians and again by the Athenians in Sicily in 413 BCE. However, the era of heavily armoured hoplites neatly arranged in two files and slashing away at each other in a fixed battle was over. More mobile and multi-weapon warfare now became the norm. Cavalry and soldiers who could throw missiles might not win battles outright but they could dramatically affect the outcome of a battle and without them the hoplites could become hopelessly exposed.

When all of these rituals were out of the way, fighting could commence but even then it was routine to patiently wait for the enemy to assemble on a suitable plain nearby. Songs were sung (the paian - a hymn to Apollo) and both sides would advance to meet each other. However, this gentlemanly approach in time gave way to more subtle battle arrangements where surprise and strategy came to the fore. What is more, conflicts also became more diverse in the Classical period with sieges and ambushes, and urban fighting becoming more common, for example at Solygeia in 425 BCE when Athenian and Corinthian hoplites fought house to house.

Strategies and deception, the ‘thieves of war’ (klemmata), as the Greeks called them, were employed by the more able and daring commanders. The most successful strategy on the ancient battlefield was using hoplites in a tight formation called the phalanx. Each man protected both himself and partially his neighbour with his large circular shield, carried on his left arm. Moving in unison the phalanx could push and attack the enemy whilst minimising each man’s exposure. Usually eight to twelve men deep and providing the maximum front possible to minimise the risk of being outflanked, the phalanx became a regular feature of the better trained armies, particularly the Spartans. Thermopylae in 480 BCE and Plataea in 479 BCE were battles where the hoplite phalanx proved devastatingly effective.

At the Battle of Leuktra in 371 BCE Thebian general Epaminondas greatly strengthened the left flank of his phalanx to about 50 men deep which meant he could smash the right flank of the opposing Spartan phalanx, a tactic he used again with great success at Mantineia in 362 BCE. Epaminondas also mixed lighter armed troops and cavalry to work at the flanks of his phalanx and harry the enemy. Hoplites responded to these developments in tactics with new formations such as the defensive square (plaision), used to great effect (and not only in defence) by Spartan general Brasidas in 423 BCE against the Lyncestians and again by the Athenians in Sicily in 413 BCE. However, the era of heavily armoured hoplites neatly arranged in two files and slashing away at each other in a fixed battle was over. More mobile and multi-weapon warfare now became the norm. Cavalry and soldiers who could throw missiles might not win battles outright but they could dramatically affect the outcome of a battle and without them the hoplites could become hopelessly exposed.

All credit and sources: http://www.ancient.eu/Greek_Warfare/

http://scottthong.files.wordpress.com/2007/05/800px-phalanx.jpg

http://d2vqx76lplv3ab.cloudfront.net/27/46/i62473767._szw270h3500_.jpg

http://scottthong.files.wordpress.com/2007/05/800px-phalanx.jpg

http://d2vqx76lplv3ab.cloudfront.net/27/46/i62473767._szw270h3500_.jpg